Whose health data is it anyway?

The government is holding off on grabbing our GP records...for now.

Welcome to Keeping the Receipts — a newsletter from the Citizens, written this week by Alice McCool and Max Colbert. You can read about the mission behind this here.

If you like what you see, consider forwarding it to a friend or two. Or to support our mission, please consider signing up to the paid version.

This was the week the government was supposed to get its hands on the medical data of every GP patient in England. The deadline for the largest data grab in NHS history was 1 September but, thanks to our legal challenge, protests from the medical community, and the whopping one million people who opted out of the proposed data-sharing scheme in just a month, their plan has been stopped in its tracks.

Under the proposed General Practice Data for Planning and Research (GPDPR) scheme, GPs would have been required to hand over the private medical records of 55 million patients to be stored on a central database which could then be shared with unspecified “third parties”.

On 19 July, the government sent a letter to GPs in England postponing the data grab until further notice. The Citizens was part of the coalition that threatened the government with legal action over the plans, so we celebrated the news as a BIG WIN.

While we agree that this data could be used to save lives, the way the government and NHS Digital were going about collecting it raised one too many red flags for us. Here’s a short film we made with palliative care doctor Dr Rachel Clarke in June, explaining why we should be worried:

Trust me I’m a doctor…on the ground in Tower Hamlets

Dr Clarke was not the only member of the medical community to speak out about her concerns. We teamed up with The Independent this week to report on the GPs in the East London borough of Tower Hamlets who made a stand, refusing to hand over patient data until they were certain it was safe to do so.

“My rights are the same as patients’ rights, because everyone's a patient. And we'd want the same thing for us,” said Dr Osman Bhatti, one of the GPs behind an open letter to the government. He told us that as a patient you should “know what's happening with all of your data and who's looking at it.” For example, a diabetic patient might be happy for their data to be shared for medical research into the number of diabetics in their area, but they might not want it shared with an insurance company which would penalise them for their condition.

And for minoritised communities like those Safia Jama works with at the Women's Inclusive Team in Bethnal Green, trust in the system is already so precarious that it’s not hard for them to imagine what could go wrong if their information was shared further.

“Many women tell us they can’t tell their GP their whole story, but for years we’ve been saying they should trust them, and that what you say is confidential,” Safia told us. She said that the women she’s been working with are finally “opening up and getting help”. But she’s concerned that those who already face barriers accessing care will quickly lose that trust if they find out their private records are going to be shared. Watch this clip of Safia explaining why the issue of patient confidentiality is so important:

We cautiously welcome the news that the government has conceded on some of our demands, outlining several ‘tests’ that would need to be met before patient data is collected, including an opt-out option and a public awareness campaign:

Our NHS is home to an unusually rich and comprehensive dataset that, in the right hands, could allow breakthroughs in medical research. Many of us would be willing to contribute our data if it was going to advance research into conditions and diseases that affect us all, or improve NHS service delivery. But there are three key questions we still need answers to:

How are the public going to be informed about all this?

If you were aware of the impending data transfer, you probably came across it through the ‘opt-out’ forms shared on social media. But many are still in the dark as the government hasn’t yet written to households to explain the planned changes, or how to opt out from the process.

According to a Which? survey in July of nearly 1,700 people in England, only 55% had heard of the scheme. Of those who hadn’t heard of it, 40% said that they would now want to opt out having been made aware of it.

It’s excellent news, then, that the government has now promised to do more to increase public awareness, but they’re still refusing to commit to writing to all patients about the data upload. We know this kind of communication is possible; they can do it for tax purposes, so why is this different?

What if the private companies already linked to the NHS get their hands on our health data?

Speculating on the impact health data sharing could have on our society can feel like an episode of Black Mirror. We’ve already seen the data of 180,000 patients shared with one of the world’s largest tobacco companies and the HIV status of a patient released in a data breach.

Then there’s the increasing involvement of US firm Palantir in the UK. The company has ties with security and immigration agencies in the United States, and was hired by the Cabinet Office last year to build a “border flow” tool-kit in a new Border Operations Centre combining data from seven government agencies. The firm already has its hands on our COVID-19 data.

This summer we published an investigation in the Byline Times into Palantir and Faculty, which have been awarded public sector contracts worth over £100 million:

Palantir is one of a number of firms tasked with processing information fed into the COVID-19 datastore, and built the platform upon which it sits. Its first government deal (ushered through under the auspices of tackling COVID-19) was awarded for £1. It was then extended for a further four months for £1 million.

The government originally claimed Palantir’s involvement would be temporary. But in just under a year, it has won four separate agreements from the NHS and Department of Health and Social Care, worth almost £25 million, and giving them access to huge reams of patient information. Following legal action from openDemocracy and Foxglove Legal, the government has agreed to consult the public regarding any further deals with Palantir.

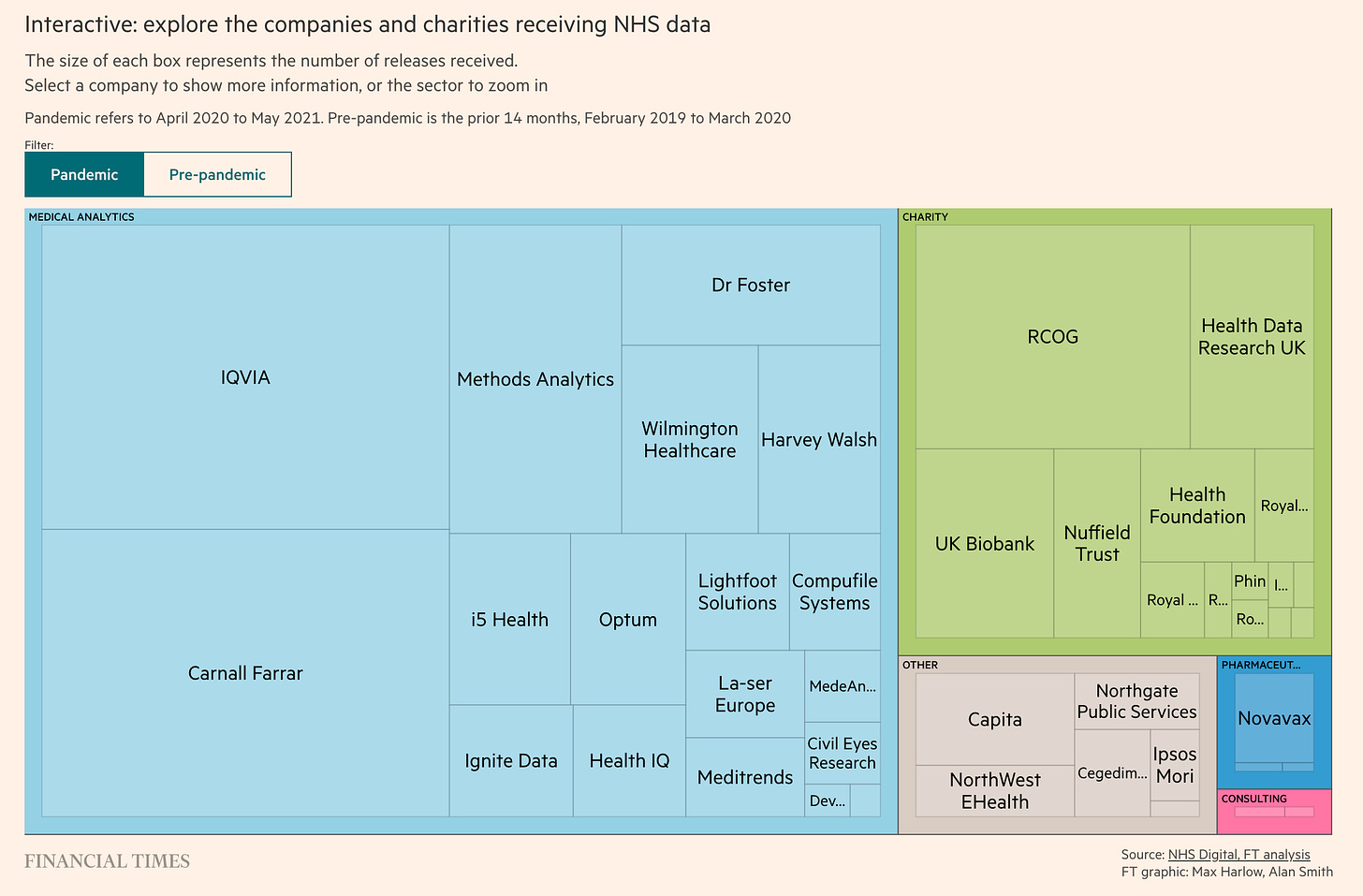

Will companies like Palantir get access to our GP records? And does corporate access to our data put our health service at an economic disadvantage when drugs or products are developed using patient data? More on this in a recent Financial Times investigation:

Why do we need a nationwide pool of data?

The GPDPR will make NHS Digital the ‘data controller’ - taking control away from GPs who can currently define how the information is used locally and communicate this with patients.

“As a government agency they can link it to any data: social history, medical history, insurance history, and so they can combine that together and then potentially sell it on,” Dr Osman Bhatti told us. Here he explains the safeguards he’d like to see in place before consenting to hand over patient data:

Plans for a nationwide pool of data raise questions about the government’s motivations. Is this to improve planning, commissioning and research for the NHS, or for corporate interest? Or is it for sharing with other government departments - which could result in criminalising people who are just trying to access healthcare?

NHS Digital told us that information about what is said in the GP consulting room will not be shared and that only “coded data” is collected and not written notes. A spokesperson said: “Patient data is vital to healthcare planning and research. It is being used to develop treatments for cancer, diabetes, long COVID and heart disease, and to plan how NHS services recover from COVID-19.

“We are committed to this programme and take our responsibility to safeguard data very seriously. Organisations using the data may be public sector bodies, charities or commercial organisations. They must all have a legal basis and legitimate need to access the data for health and care planning and research purposes.

“Data will only be accessed within a Trusted Research Environment. TREs provide approved researchers with access to the de-identified data that they require for ethically and legally approved research projects in a secure environment, providing greater assurance that all data is handled securely and sensitively.

“We have listened to feedback on proposals and will continue working with patients, clinicians, researchers and charities to inform further safeguards, reduce the bureaucratic burden on GPs and step-up communications for GPs and the public ahead of implementing the programme.”

It’s a step in the right direction. Because without these safeguards, and a comprehensive public information campaign, trust in our health system could crumble. This is exactly what GPs like Dr Bhatti fear most. If the trust between doctor and patient is compromised, public health as a whole is at risk.