Welcome to Keeping the Receipts— a newsletter from the Citizens, written this week by Iain Overton and Sian Norris. You can read about the mission behind this here.

If you like what you see, consider forwarding it to a friend or two. And if you’ve been reading it for free and want to support our mission, please consider signing up to the paid version.

An exclusive investigation into the profile of elite Conservative donors by The Citizens, published in full with the Byline Times last week, revealed that a quarter of those who have given at least £100,000 in a single donation have been recognised with an honour, title, or place in the House of Lords. Indeed, when it comes to the top donors – those donating more than £1.5 million to the party – our investigation showed that 55% had been honoured with titles or awards such as OBEs and MBEs.

We asked Citizens reporter Alice McCool to make a short film explaining some of the findings of our investigation. Watch here:

This might, in itself, be shocking enough. But sometimes, the story is as much about what we don’t know, as what we do.

Of the 286 donors who gave single gifts larger than £100,000 to the party since 2010, there were 26 names that we simply could find nothing certain about. This is because the Electoral Commission – the elections watchdog, which monitors party donations – only records the forename and surname of donors, and sometimes their title. It is therefore impossible to reliably identify donors who have fairly generic names – such as ‘John Smith’ or ‘Dave Brown’.

This makes it difficult to determine exactly who is giving big money to political parties, and the nature of the relationship they have with the parties themselves.

Many of the elite donors identified in this investigation used multiple versions of their names. For example, the Conservative Party’s largest elite donor, Sir Michael Farmer, had donations listed under his title, just his forename, and just his initials. Other donors appeared to give money under their wives’ name.

Whatever the reason for this, this lack of transparency is bad for democracy and makes a mockery of how the UK records donations and therefore tracks their influence.

The Conservatives have already faced scrutiny over the extent of Russian influence on British democracy and its MPs. Although its publication was delayed until after the 2019 General Election, the Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament’s ‘Russia Report’ revealed how 14 government ministers – including Chancellor Rishi Sunak and COP 26 President Alok Sharma – had received funding from donors linked to Russia, either directly or via their constituency parties. Lubov Chernukhin, who our investigation revealed as one of the few female elite donors, was one of the people named in the Russia Report.

All political parties receive donations. Even party membership is a form of donation, albeit a modest one. The Labour Party is famously supported by trade unions, while Lord David Sainsbury made a large donation to the Liberal Democrats in 2019.

But there is a reason the super-rich tend to favour the Conservative Party with their gifts – and that is because the Conservative Party tends to favour the super-rich.

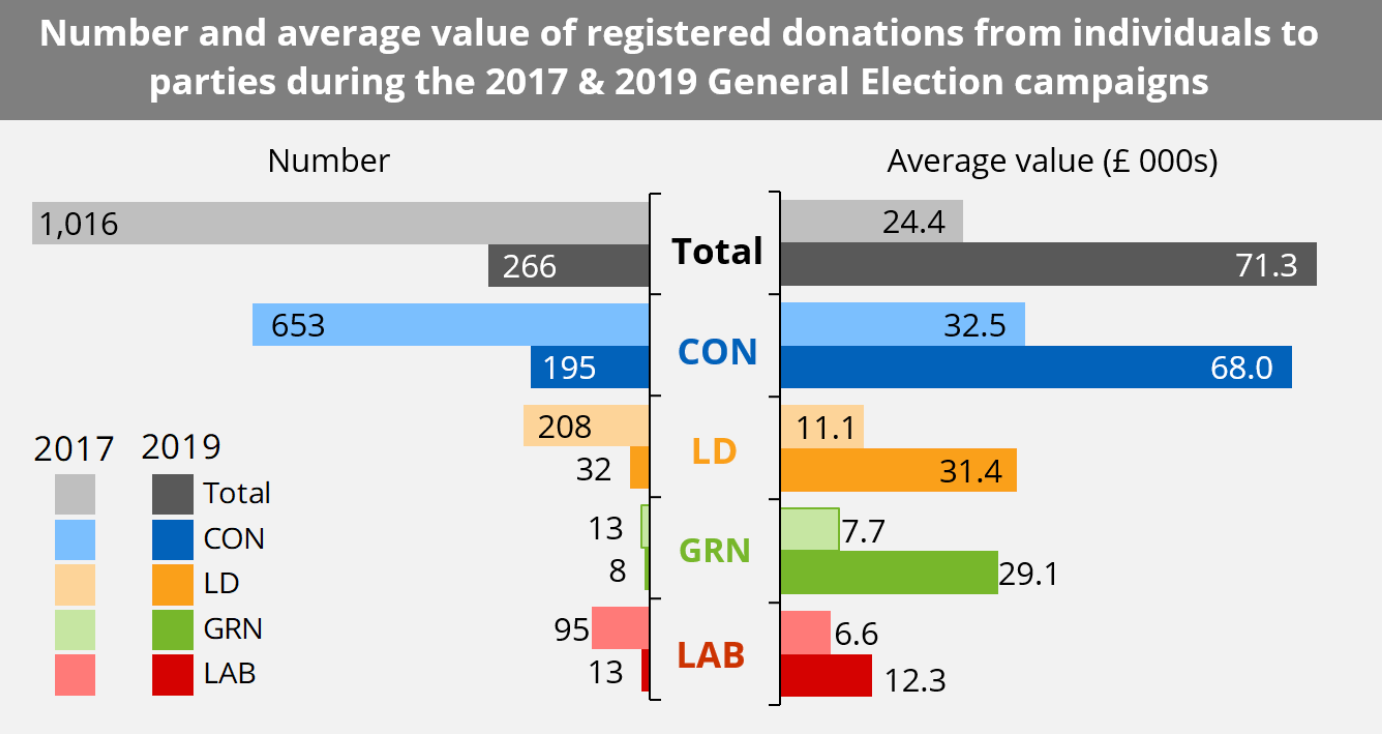

It is notable that the average Conservative ‘elite’ donor (one who has given at least £100,000 in a single donation) has donated more than £500,000 in the past decade. This average is almost three times the amount of the total funds the Labour Party received from all individual donors combined during the 2019 General Election

Decreasing membership numbers in the Conservative Party means that it is becoming ever more dependent on its biggest backers. This risks having grave consequences for democracy, as wealthy donors start to expect a return on their investment.

Conservative MPs such as Grant Schapps claim that donations don’t translate into political influence. But when is it ever that simple? From Brexit to the smoking lobby, construction to free ports, a variety of niche interests linked to large donors are making political headway – often through a network of free market think tanks that surround Westminster.

If the trends in political donations continue to follow the current path, the UK risks moving closer to the US model – where ‘dark money’ from wealthy business interests fuels parties and holds sway over policy. This has been particularly disastrous with regards to the fossil fuel lobby, which has spent billions of dollars in Washington D.C. to frustrate progress on the climate crisis.

Our investigation offers some clear recommendations that can improve transparency in the donation system and therefore protect democratic processes.

First, all donors should have to provide their date of birth, as well as a forename and surname, and only be allowed to donate under one name. This would make it easier to identify those with generic names, and end the practice of spreading donations across multiple identities.

The Electoral Commission should also provide a cumulative total amount of donations made by individuals. This means that, if a person has given five donations of £25,000, it is immediately obvious that they have donated £125,000 in total.

Finally, donations made via companies should not receive tax breaks. When a donation is made through a corporation, it should have a named individual attached to it and that named individual should be the person with significant control of the company. Again, this will make clearer who is giving the money and how much they have given.

However, given that the Elections Bill seeks to severely weaken the powers of the Electoral Commission, the potential to improve democratic accountability is under greater threat than ever.