'Democracy is not guaranteed'

Q&A with 'My Little Crony' creator Sophie Hill on the UK's 'devastating failure of governance' and why cronyism is a threat to our democracy

Welcome to Keeping the Receipts— a newsletter from the Citizens, written this week by Joanne O’Connor. You can read about the mission behind this here.

If you like what you see, consider forwarding it to a friend or two. Or to support our mission, please consider signing up to the paid version.

Earlier this month the New York Times ran a piece on cronyism in the UK and how the established system of ‘gentleman’s agreements’ which exists in place of hard and fast legislation is being exploited by Boris Johnson’s government for the benefit of Tory party allies and donors.

While the media spotlight has, quite rightly, been focused on the unfolding catastrophe in Afghanistan this summer, the allegations of influence-peddling continue to seep out, from reports by the BBC that David Cameron earned as much as $10m lobbying for Lex Greensill’s finance company, to a series of stories in the Financial Times and various media outlets about the role of the Conservative Party’s well-connected co-chairman Ben Elliot in creating an “advisory board” for wealthy donors who receive regular access to the prime minister and Rishi Sunak.

Hannah White, deputy director of the Institute for Government, is quoted in the New York Times as saying that Britain is at “a dangerous moment” and the current system is “not terribly fit for purpose”. Just how unfit has been exposed repeatedly since the start of the pandemic and it’s something that we at The Citizens have been attempting to keep tabs on with our Keeping the Receipts project. Since May we’ve been logging instances where rules have been broken, ministerial codes breached and norms flouted in a public spreadsheet devoted to the topic of cronyism.

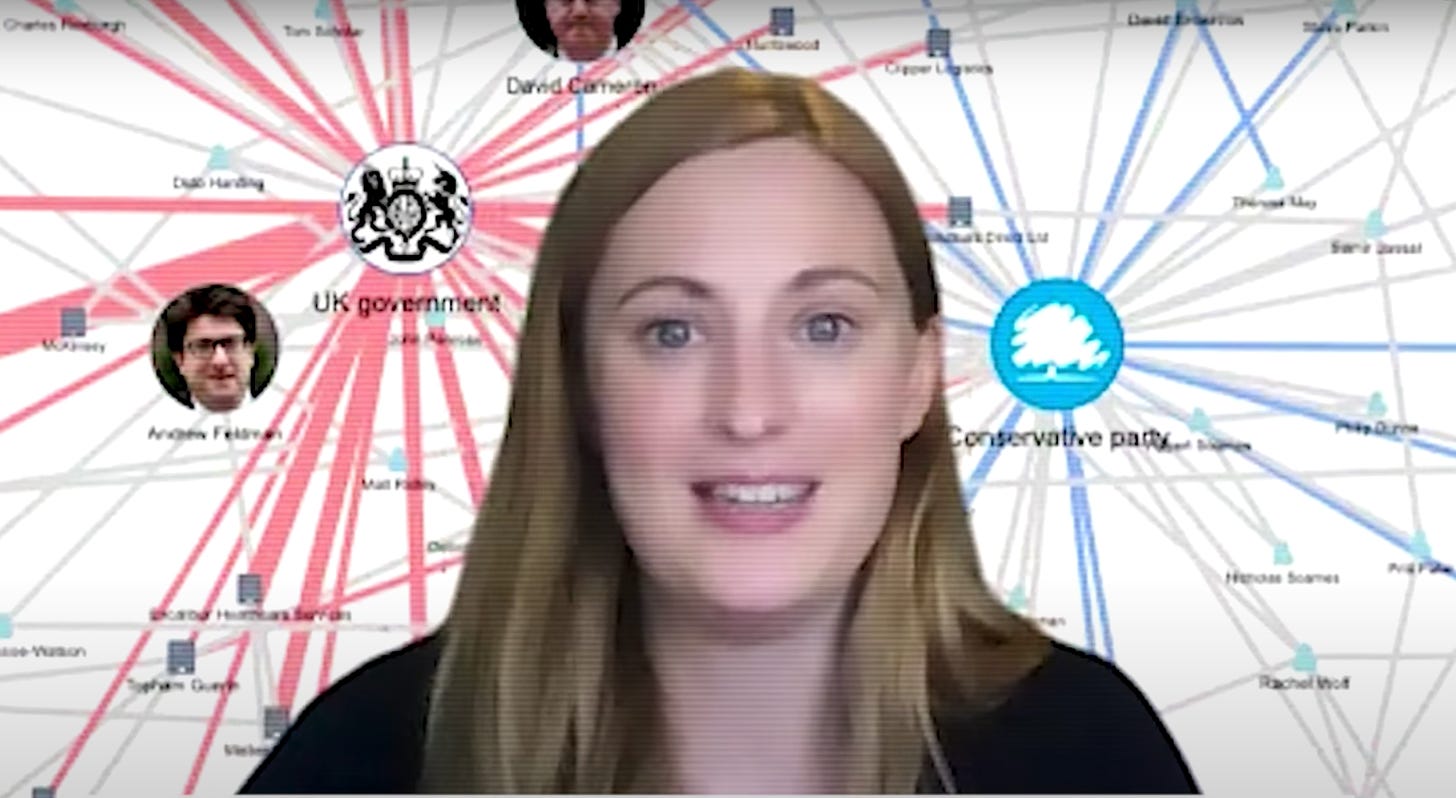

It’s a work in progress, much like My Little Crony, the extraordinary data visualisation created by Harvard political science PhD student Sophie Hill to show the intricate web of connections between Tory politicians and firms winning government contracts. Initially conceived as a “fun little interactive thing” to share with a few friends last November, the interactive map quickly went viral on social media and has been cited twice in the Houses of Parliament.

We spoke to Sophie about the inspiration behind the project, why cronyism poses a serious threat to our democracy, and what we need to do to fix it.

What was the inspiration for My Little Crony?

I launched My Little Crony in November last year. As a Brit living in the US, I was sitting on the edge of my seat waiting for the presidential election results to come in, which is a scary time. And I thought, I need a side project that's going to keep me occupied, something useful, that's nothing to do with Trump. I'd been reading these news stories about allegations of cronyism and I just couldn't keep track of all the names or see how they added up. To me, words are not a very efficient way to describe that data. This is really a network. And when you see it all laid out, you start to see that this adds up to a systemic issue. It wasn't just one bad decision made during a crisis. It is a system of political favouritism, which is the definition of cronyism.

Why does cronyism matter?

The idea that we created a ‘VIP lane’ for politically-connected firms goes against every set of anti-corruption best practices that's ever been written. By creating that system, the government incentivised all kinds of opportunistic behaviour. There’s a sense that government officials, our representatives, are behaving with impunity. They really don't even care how bad it looks. It's offensive to us as citizens, but it's also a really big problem because a lot of our mechanisms for holding officials accountable depend on them ultimately being forced to resign through public pressure and media scrutiny.

In the last 18 months a series of ministerial scandals have come to light that, not so long ago, would have been deemed grounds for resignation. What has changed?

Norms can break down much more easily than you think. You can be in a good equilibrium, where we have a ministerial code, we have an independent advisor that tells the minister if they've broken that code, and the ministers are expected to hand in their resignation. But all it takes is one case where those rules aren't enforced, which we had with Priti Patel, who was found by the independent advisor to have broken the ministerial code because of bullying, which is a very serious breach. She didn't resign. And so from that point on, the question facing ministers isn't “Oh, have I broken the ministerial code?” The question is “Did I do something worse than Priti Patel?” That really changes the calculus. It only takes a few poor decisions to take us into a delicate place where we have very few ways of keeping ministers accountable.

What surprised you the most when you were researching My Little Crony?

I think the most surprising thing was seeing the role of these informal advisors, who sort of infiltrated government with a very ill-defined set of responsibilities, and were able to do whatever was advantageous to them and their private business. The Greensill scandal was a great example of how baked in this kind of cronyism is. So Lex Greensill was wandering around Whitehall. Apparently he had a desk and a computer. And many officials say that he was never actually formally employed, but he somehow managed to sit in on meetings and act like an advisor. And what that tells you is that there is a culture of accepting these types of very informal roles in government and this is a huge anti-corruption red flag.

Does using terms like ‘cronyism’ or ‘chumocracy’ risk diminishing the seriousness of the problem?

People often say, just call it what it is – corruption. But I think cronyism and chumocracy do have a specific connotation, which is that, in most cases, the public officials were not directly benefiting themselves. They were awarding contracts and benefits to their friends or acquaintances. And of course, maybe they did that with the expectation of some benefit in return, maybe they're repaying a favour. But I think it is important to capture that distinction, because it's relevant for the kinds of policies we might put in place to stop it. If we were really worried about public officials personally benefiting, then we would probably be thinking more about financial disclosures.

So I think the terms are helpful, but the overall bracket I would put this under is failure of good governance. And I think that's quite devastating. Because what happened throughout this pandemic is that the government broke fundamental rules. We have systems to insulate the civil service from political pressure. That's a really important anti-corruption practice and the government just abandoned this.

I don't think there's some criminal mastermind at the centre of this. I think it really is a case of revealing how fragile our institutions were, and how easily a few bad decisions from those at the top can filter down and corrupt the whole system. And that rot can spread incredibly quickly. And it's going to be very difficult to get rid of.

So if the system is broken, how do we fix it?

The first thing I would like to see is the government complying with its legal obligations around transparency. 73% of the contracts awarded during the pandemic were not published within the 30 day legal timeline. A number of those weren't published even 100 days after they were awarded. There's really no justification for that, aside from cynicism and avoiding scrutiny.

Number two would be strengthening the way that we deal with lobbyists. The Greensill saga has unavoidably shown us that the current system doesn't work. David Cameron was a lobbyist for Greensill. Under our current rules, he doesn't even have to register, because he doesn't work for a specialised lobbying firm. That's a ridiculous loophole.

The third thing, which I think is critical, is that we stop employing people as unpaid advisors. Being in government is really hard work. We should pay a competitive salary to get great people in these key positions. We should not allow people to treat this as some type of part-time jaunt where they mosey around seeing where they can drum up business for their other side businesses.

Other than voting, what can individuals do to play their part in ensuring a healthy democracy?

In order for democracy to be healthy, we need a bunch of different moving parts to be working together, sometimes in an adversarial way. We need a strong opposition. We need independent media. We need a vibrant civil society. And we need all of those things. So I think this reminds us that democracy is actually a really hard system to maintain. And that democracy isn't something that you just have and, once you've got it, there you go, like riding a bike. It's something that is reproduced over time, and it's not guaranteed. The biggest thing we have to avoid is complacency.

What comes next after My Little Crony?

I'm not sure if My Little Crony will ever end. My guess is there's probably quite a lot more still to come out. At a certain point, I think it will be too dense to even see anything. When you look at this image and you see all these inter-connections, it's just this little reminder that we think we have a nice professionalised, institutionalised civil service and government, but what we really have is this tangled web of old school mates and uni mates and spouses and lobbyists. It's very messy.